City College of San Francisco Judo Club

menu

Assignments

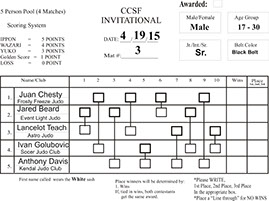

Tournament Management: Using 2 Pool "Fight" Sheets

Tournament Management: Pool "Fight" Sheet

Pool Sheet

- Method of Elimination

- Pool system of competition will be used: 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 person pool

- Contestants are grouped in pools according to the following criteria

- Sex: Separate grouping for Male and Female

- Age: The age group

- Belt Color: Similar belt color

- Weight: The contestants are group with a 10 lbs difference between the lightest to heaviest.

- First Name called wears the "White" Belt

Course Syllabus

Judo Technique Inventory

Judo Etiquette, Hygiene, and Safety

Judo Practice

Judo practice has many rules of etiquette, manners, and ethics. Above all, judo students learn important values of respect, respect for their instructors/sensei; their practice partners; the officials and referees of judo; the families and friends of judo classmates; and above all, themselves.

Judo students learn to be attentive, and develop a good work ethic that they can carry with them into others parts of their lives. Judo students learn modesty and fairplay.

Values related to sincerity, courage, and commitment are fostered through the actions of attack and defense during judo practice. Judo students learn to persevere in a physically and mentally demanding training that fosters emotional control and diligence.

Judo students greet one another with respect and courtesy.

In short, judo students learn much of the social etiquette necessary to become solid citizens of the world.

Rituals - Bowing

Of the many rituals that are a part of judo, perhaps none is clearer and poignant than the bow. In judo, bowing is a signal of respect. Judo students bow when entering and leaving the dojo. They bow to the teacher at the beginning and end of practice, to give thanks and appreciation to the sensei for their teaching.

The entire class, including the teachers, often bows at the beginning and end of class to the head area of the dojo containing all the objects of respect. Before practicing with each other, students bow to show respect to each other, and they bow once again at the end to give thanks for the workout.

In formal judo matches, contestants bow at the beginning and end of the match, to signify respect and courtesy for each other as opponents, and to the institution and rules of judo, which fosters fairplay and sportspersonship.

Bowing is also a posture of humility, gratitude, and appreciation. Through their judo training, students literally bow hundreds of times a week. Over the years, bowing will become an integral part of your attitude and perspective on life, and others. It is in this fashion that judo molds its students to be admirable citizens, both on and off the mat.

Personal Hygiene

Personal hygiene is a must in the dojo.

- Your uniform should always be clean and in good repair

- Do not practice shirtless.

- Fingernails and toenails should always be trimmed short

- All sharp jewelry should be removed prior to practice

- Long hair should be tied back out of the way (braids or pigtails preferably)

- Deodorant can be used prior to practice, but strong cologne should not.

- Bandage all cuts and scrapes prior to practice

- Bring a towel with you and use it rather than your uniform or constantly dripping sweat onto your partner and the mats

- Do not wear heavy makeup as it will smear onto the uniforms worn by you and your partner

Dojo hygiene is the responsibility of the dojo members

- Pick up after yourself. Throw you trash in the trash cans.

- if you see trash that is not yours, pick it up and throw it away anyway.

- if there are any blood spills, use the disinfectant to clean it up immediately. (if it’s your blood and you are capable of cleaning it, please do so)

History

ENTER JIGORO KANO

Jigoro Kano was born on October 28, 1860; six years and seven months after Japan was forced to open its doors to the West by Perry's second visit in March 1854. Japan was in a state of turmoil as it struggled to adjust to the rest of the world that had not been asleep. In 1867, Emperor Meiji was installed and was the symbol of modernization. Tokugawa Yoshinobu was the last of the Tokugawa shoguns but was forced to resign and with him the feudal system is also abolished.

Jigoro Kano was born on October 28, 1860; six years and seven months after Japan was forced to open its doors to the West by Perry's second visit in March 1854. Japan was in a state of turmoil as it struggled to adjust to the rest of the world that had not been asleep. In 1867, Emperor Meiji was installed and was the symbol of modernization. Tokugawa Yoshinobu was the last of the Tokugawa shoguns but was forced to resign and with him the feudal system is also abolished.1877 marks the entry of Kano into Toyo Teikoku University, now (Tokyo University). Kano's education to this point was extensive for the period. He was trained in Confucian classics and studied English under Mitsukuri Shuhei, a renowned thinker of the day. Much of what Kano thought can be easily read for he kept much of his notes in English. He also had a penchant for math but what he wanted to do dearly was to develop his body, or at any rate defend himself for he was slight and frail in stature. As a means of physical culture and training he enrolled in a jujitsu school, much to his father’s dismay.

Hachinosuke Fukuda, grandfather to famed 10th dan, Keiko Fukuda, was Jigoro Kano's first jujitsu instructor. Tenshinshinyo ryu jujitsu was mostly comprised of pins, chokes and locks, and was practiced through formal movement patterns known as kata or form. Kano was so adept after just two years of training he was asked to perform for the visiting Ulysses S. Grant in 1879.

Wanting to learn more he enrolled in Kito ryu jujitsu in 1881. Kito-ryu was markedly different from his earlier style called Tenshinshinyo ryu for it concentrated in throws and practice did not rely solely on kata but on free movement. Tsunetoshi Iikubo was the instructor and had a great influence on Kano for he stressed the soul as well as the body.

1882 was a momentous year. Japan built its first railroad, and Jigoro Kano at the young age of twenty two founded the Kodokan. It was a humble beginning with only nine students in a ten tatami” room at Eishoji Temple. One tatami is equal to 1meter by 2 meters.

But Kano is persistent, intelligent, and dedicated. Trying to decide on a system of training for their officers, in 1886 the Tokyo police force sponsored a tournament in which some of the leading schools of the day were invited to participate. The Kodokan, with the exception of a draw or two, wins all other matches and sparks an interest in the public eye.

Jigoro Kano, educator, statesman, and founder of modern judo, did much in the development of Japan’s fledgling, Meiji era education system.

Jigoro Kano, educator, statesman, and founder of modern judo, did much in the development of Japan’s fledgling, Meiji era education system.Kano was a leader amongst men and possessed the right qualities at the right time. Trained in the classics, yet studied and was adept at English, loved mathematics, but more than these individual skills was his ability to fuse ideas together that created a better sport. Always the valiant eclectic, he was not afraid to try something new; at 22 years of age, he was appointed as a professor at Gakushuin University. In addition to this position he founded not only the Kodokan but Kanojuku, a preparatory school, and also the Koubunkan an English language school all within the same year, 1882. In 1899 he founded the Koubungakuin a school for foreign students from China. Noticing a lack of an official sports organization in Japan in 1911, he creates the Japan Athletic Association.

Between 1882-1911, Kano begins to excel as an educator and in four years time became the head instructor at Gakushuin University. 1889 marked Kano's first of many trips abroad where he studied European educational systems as an Attaché of the Imperial Household. As if he didn't have enough to do in the world, Kano becomes the principal of a high school in Kumamoto in 1891. Then in 1893, returns to Tokyo and assumes the presidency of a teachers college (now Tsukuba University).

Through the years he distinguishes himself as an educator, physical educator, statesman, writer, philosopher and linguist. In 1902 and 1905, he represents the Ministry of Education and visits China. His college studies in Political Science and literature aid him greatly in establishing him as a statesman.

All these abilities came to fruition in 1909 when an invitation from the International Olympic Committee (IOC) to Japan to participate in the Olympic movement resulted in the only possible choice for a representative, Jigoro Kano. Thus, he became the first Asian member of the IOC. Later in his career he is accorded entry into The House of Peers and given the rank of Count.

The Development of Judo

Japan was quickly making strides to catch up with the rest of the world after having been asleep for some two hundred and sixty five years. The basic mood of the nation at that time was “Out with old in with the new.” Thus, jujitsu was considered out of step with the times.

It took a man of action to breathe life back into an art form that was about to be discarded. There were very few who could explain by words, what many a master of the arts intuitively understood when executing phenomenal maneuvers. Nor were there individuals who could translate into words the common denominators that made these arts important not in terms of self-defense but of living life. Kano fortunately could and did.

To more accurately assess the thinking of Jigoro Kano and the evolution of how he came to explain judo as he did, one would have to study his writings, the dates they were written, and study them within the context of the social events that may have influenced his thinking.

The Meiji restoration era, nationalism, empire building, his education, and his travels abroad shaped the words that explained judo and its broader purpose.

The Meiji restoration era, nationalism, empire building, his education, and his travels abroad shaped the words that explained judo and its broader purpose.Japan had just emerged out of the isolationism imposed by the Tokugawa regime. It found itself at the back of the line in technological advances and understood it was in a very weak position. It wanted to understand the West, and needed to find a way to quickly catch up with the rest of the world least they be victimized by their neighbors. To aid in this endeavor the newly installed emperor Meiji dedicated his efforts to modernization.

Large scale government reforms were made in which education, media (then Newspapers), transportation, communication, the making of a national army were instituted in an effort to create a strong national consciousness that could stand proudly amongst neighboring nations.

Things were moving fast in Japan and much was being accomplished in a very short time. Within 27 years after the installation of Emperor Meiji, Japan had become an industrialized power. So much so that in Asia it was the dominant power and proved itself in battles with China in 1894 and Russia in 1904, coming out the winner in both instances.

In this climate of success and of building national pride it was important to maintain strong bodies and good discipline. It fell to Jigoro Kano the educator to add to the strength of his nation by incessantly writing and publishing articles emphasizing the benefits of judo and the martial arts, not only as a means of strengthening the body, but through its practice learning many valuable lessons that could be applied to daily life.

In a sense the spirit of the samurai was kept alive through the reintroduction of the martial arts through education. His writings and philosophy of judo as a sport of far reaching qualities differentiated it from jujitsu.

Inherent in the activity was the idea that if one used his body efficiently, although he may be smaller, he could overcome a larger adversary who did not. This concept not only applied to the diminutive Jigoro Kano but appealed to the small island nation of Japan as its foes seemed always larger. Brousse and Matsumoto in Judo a Sport and Way of Life wrote, “He sensed and developed the guiding principle behind jujitsu where others had seen a collection of techniques.” The ultimate goal was to make the most efficient use of mental and physical energy. It is little wonder that he was to come up with the maxim, Seiryoku Zenyo, “the best use of one’s energy, vigor, vitality”, an ideal which is essential to any vigilant culture or nation much less a sport.

The Success of Judo Rather Than Jujitsu

Many will say that the biggest difference that led to the success of judo rather than jujitsu in Japan was the 1886 contest held by the police in which Kodokan judo prevailed over all the other systems of the day. This may be true in part but there have been many victories by one organization over another that have not lasted the test of time. One of the overriding reasons for the success of judo was Kano's position as a major player in the development of education during the Meiji era. He was well educated, experienced, and traveled abroad specifically to learn about western educational systems. He was the expert and he was in charge of developing the country’s teachers; teachers who would of course learn judo at school, then turn around and teach it at a middle school, high school, or college. To this day judo is taught in schools throughout Japan as part of the physical education program.

Another reason for judo's success was Jigoro Kano himself. He was a tireless recruiter of judo practitioners and supporters. Everywhere he went he spoke of the many attributes of judo: fitness, character building, economy of motion, self-actualization, self-defense, and a model for a way of life. He himself was the embodiment of the attributes of which he spoke. Kano also had a keen awareness of timing and knowledge of who were the change agents who he could entrust to influence the masses.

Another reason for judo's success was Jigoro Kano himself. He was a tireless recruiter of judo practitioners and supporters. Everywhere he went he spoke of the many attributes of judo: fitness, character building, economy of motion, self-actualization, self-defense, and a model for a way of life. He himself was the embodiment of the attributes of which he spoke. Kano also had a keen awareness of timing and knowledge of who were the change agents who he could entrust to influence the masses.He utilized the opportunity to speak with leaders such as Pierre de Coubertin, Originator of the Modern Olympic Games, John Dewey, one of the architects of modern education in the United States and many others. These people outside of his country were introduced to judo, not just for it physical characteristics, but more so for its positive effects on the improvement of the quality of life for society through its practice.

Jigoro Kano’s command of the English language should not be forgotten here, for it opened the door to introducing the then little known sport of judo to the west. According to Naoki Murata, head librarian at the Kodokan. “Many of Kano’s notes of judo were written not in Japanese but in English.”

Although it is not often mentioned as a reason for judo's rise as an exportable item we must not discount the effect of the two wars that suddenly placed Japan in the forefront of public curiosity. First China, then Russia, two large countries succumbing to the smaller Japan. Moreover, Russia although having its own internal problems, was once considered a white European power. Could it be that some secrets out of the East, could be used to win the war over its larger opponents? These same secrets could also be found in this mysterious activity called judo? Here too, the larger individual could be overcome by the smaller. At any rate people flocked to see this wondrous activity that the devotees were eager to teach. Especially keen on its investigation were the armed services, police, and the elite.

Although it is not often mentioned as a reason for judo's rise as an exportable item we must not discount the effect of the two wars that suddenly placed Japan in the forefront of public curiosity. First China, then Russia, two large countries succumbing to the smaller Japan. Moreover, Russia although having its own internal problems, was once considered a white European power. Could it be that some secrets out of the East, could be used to win the war over its larger opponents? These same secrets could also be found in this mysterious activity called judo? Here too, the larger individual could be overcome by the smaller. At any rate people flocked to see this wondrous activity that the devotees were eager to teach. Especially keen on its investigation were the armed services, police, and the elite.On a more clouded note, the ability of judo and jujitsu to infiltrate the upper crust of society gave it importance in the Meiji era as a means of understanding foreign cultures and was sometimes used as an unofficial information highway through which crucial bits of information gleaned from casual conversations aided in making major policy or strategic decisions. For foreign countries, it also allowed a glimpse into Japanese culture as well. Thus, the exportability of judo and jujitsu was yet another factor to consider.

Educational Tool

While many looked upon judo and jujitsu as a means of unarmed combat Dr. Kano came to view his judo as a ready-made educational tool; first to develop his nation and to eventually benefit the world. In its practice, he could see economy of motion, the interplay of individual forces creating something bigger than its individual parts, the development of the individual into something he would not otherwise be, but for the practice of this physical activity. Kano's broader view of this activity, when he compared it to other sports, prompted modifications that could help it survive and be included as a sport and an educational tool. Hence, methods of falling were improved and practiced, dangerous techniques were excluded from its practice, rules of gamesmanship began to replace the air of dueling to determine superiority. These issues aided the acceptance and transformed judo from a cultural martial art to a modern sport.

JUDO’S SPREAD AROUND THE WORLD

Yoshiaki Yamashita

In various parts of the world as practitioners of judo fortuitously or purposely ventured out, there was always a curious audience. One of the first to take judo outside of Japan was in 1903 when Yoshiaki Yamashita was invited to the United States by Railroad magnate Graham Hill and taught at Annapolis Naval Academy. Included on his list of many important persons of the era, he was instructor to President Theodore Roosevelt who eventually earned a brown belt. A brown belt then was a very respectable rank during the time when there was not much inflation of rank. Yoshiaki Yamashita eventually received the very first 10th Dan awarded by Dr. Kano in 1935.

In various parts of the world as practitioners of judo fortuitously or purposely ventured out, there was always a curious audience. One of the first to take judo outside of Japan was in 1903 when Yoshiaki Yamashita was invited to the United States by Railroad magnate Graham Hill and taught at Annapolis Naval Academy. Included on his list of many important persons of the era, he was instructor to President Theodore Roosevelt who eventually earned a brown belt. A brown belt then was a very respectable rank during the time when there was not much inflation of rank. Yoshiaki Yamashita eventually received the very first 10th Dan awarded by Dr. Kano in 1935.Yukio Tani

In 1905, judo appeared in Great Britain in the person of Yukio Tani. There are plethoras of tales about this colorful individual as he traveled about the British Isles making a living by taking on all comers. Sometimes he would have easy opponents and sometimes not. Losing some but winning most. Sometimes he was sober other times he was not. Nevertheless, it was always interesting to see a smaller man confront larger men and come out on top.

In 1905, judo appeared in Great Britain in the person of Yukio Tani. There are plethoras of tales about this colorful individual as he traveled about the British Isles making a living by taking on all comers. Sometimes he would have easy opponents and sometimes not. Losing some but winning most. Sometimes he was sober other times he was not. Nevertheless, it was always interesting to see a smaller man confront larger men and come out on top.Gunji Koizumi

Tani was followed by Gunji Koizumi one year later. Koizumi was instrumental in the development of British judo and was the founder of the Budokwai in London in 1918. Both Tani and Koizumi were instructors there. Originally they were jujitsu enthusiasts and only after a visit by Dr. Kano in 1920 did they switch over to become members of the Kodokan. Both were also present at the incipience of the European Judo Union in 1937 when the first European Judo Championships in Dresden, Germany. The events were to inspire other continents to do likewise and the result was to eventually culminate in the creation of a world championship.

Tani was followed by Gunji Koizumi one year later. Koizumi was instrumental in the development of British judo and was the founder of the Budokwai in London in 1918. Both Tani and Koizumi were instructors there. Originally they were jujitsu enthusiasts and only after a visit by Dr. Kano in 1920 did they switch over to become members of the Kodokan. Both were also present at the incipience of the European Judo Union in 1937 when the first European Judo Championships in Dresden, Germany. The events were to inspire other continents to do likewise and the result was to eventually culminate in the creation of a world championship.Mikinosuke Kawaishi

The founding of French judo is credited to Mikinosuke Kawaishi who arrived in 1935 and introduced judo through a system based on numbers and French words rather than on difficult to remember or pronounce Japanese terminology. This plus the ingenious colored belt system did much to popularize judo in France. France lists over 500,000 registered judokas and is the second largest judo population in the world.

The founding of French judo is credited to Mikinosuke Kawaishi who arrived in 1935 and introduced judo through a system based on numbers and French words rather than on difficult to remember or pronounce Japanese terminology. This plus the ingenious colored belt system did much to popularize judo in France. France lists over 500,000 registered judokas and is the second largest judo population in the world.Takugoro Ito

In the United States during the turn of the century large pockets of Japanese settlements could be found. They were in Hawaii, then not yet a state, Seattle, and Los Angeles. Many of the immigrants left Japan in search of job opportunities and adventure. They brought with them their customs, language, and work ethics. They were successful particularly in two fields, farming, and fishing. Amongst the cultural activities of dance and flower arrangement was judo.

1907 saw the establishment of the first permanent dojo with Takugoro Ito as the instructor in Seattle, Washington. Ito was later to go to Los Angeles and is credited with the establishing of the first dojo in Los Angeles. It was named Rafu Dojo and while it is no longer there, as of 2002, the restructured 1920's wooden Seattle dojo is still standing. Between 1903 and the present, judo has spread eastward across the United States to include all races and creeds.

In 1964 the First U.S. Olympic Judo Team was represented by a Japanese American lightweight, a Jewish American middleweight, an American Indian light heavyweight, and Black American heavyweight.

In 1964 the First U.S. Olympic Judo Team was represented by a Japanese American lightweight, a Jewish American middleweight, an American Indian light heavyweight, and Black American heavyweight.Judo Organizations in the United States

Associations of black belt holders (Yudanshakai) developed first, followed by the formation of the first national organization. This was accomplished in 1952. Originally the organization was known as the JBBF or Judo Black Belt Federation but was subsequently changed to The United States Judo Federation (USJF).

The USJF's strength lies in the clustering of different dojos to provide a quality program which is grass roots oriented. In 1965, a second national organization was formed from what was originally the Armed Forces Judo Association, now known as the United States Judo Association (USJA). It was also grass roots oriented, well organized paper wise, and gave the individual clubs and their instructors more autonomy because they were usually in isolated areas of the United States where services were hard to come by. In 1980 through an act of Congress The National Sports Act of 1979 United States Judo Incorporated (USJI) was formed. It then became the direct link to the United States Olympic Committee and replaced the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU). Ultimately the two National Organizations, USJF and USJA became “A” class members and each individual State organizations as “B” members of USJI. USJI has since changed its name to USA Judo.

The USJF's strength lies in the clustering of different dojos to provide a quality program which is grass roots oriented. In 1965, a second national organization was formed from what was originally the Armed Forces Judo Association, now known as the United States Judo Association (USJA). It was also grass roots oriented, well organized paper wise, and gave the individual clubs and their instructors more autonomy because they were usually in isolated areas of the United States where services were hard to come by. In 1980 through an act of Congress The National Sports Act of 1979 United States Judo Incorporated (USJI) was formed. It then became the direct link to the United States Olympic Committee and replaced the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU). Ultimately the two National Organizations, USJF and USJA became “A” class members and each individual State organizations as “B” members of USJI. USJI has since changed its name to USA Judo.Philosophy

One of the important principles in jujitsu was a principle of “Jiu no ri.” The principle of giving way rather than opposing force. For example, if a force of 10 units were in direct opposition to another force of 3 units then, the 10 units of force would be 7 units. If instead of being in direct opposition, the 3 units returned in the same direction as the 10 unit force, a force could be turned to the advantage of 13 units. This was an explanation that was often use in reference to the application of a throw, where someone larger was rushing forward to attack and a smaller person turned and used this onrushing force against the opponent.

One of the important principles in jujitsu was a principle of “Jiu no ri.” The principle of giving way rather than opposing force. For example, if a force of 10 units were in direct opposition to another force of 3 units then, the 10 units of force would be 7 units. If instead of being in direct opposition, the 3 units returned in the same direction as the 10 unit force, a force could be turned to the advantage of 13 units. This was an explanation that was often use in reference to the application of a throw, where someone larger was rushing forward to attack and a smaller person turned and used this onrushing force against the opponent.Unfortunately, this principle did not always work well in all instances. In some examples where a choke or an arm bar, giving way may not produce the best results. Search as he did Jigoro Kano could not find a universal principle, which would work in every instance.

Kano realize through his long and arduous practice of the art that he found himself changed. He was much stronger and healthier. Because of his physical prowess, he had more confidence in himself. With more confidence, his demeanor also changed. This led him to believe the physical activity of judo could improve the character of the practitioner. Moreover, if jujitsu could improve one person why not many persons, better yet a large group, or benefit society.

Basically, these were some of the stumbling blocks Kano solved, leading to the idea and formulation of judo as a mental as well as a physical activity.

Small Judo --- Large Judo

From almost the very start, serious thought was put into what we so loosely know as the gentle way, judo. According to Asian studies professor, David Waterhouse of the University of Toronto, “The name judo, the pliant way, comes from Kito-ryu, having been long used in Jikishin-ryu, an old branch of it.” The use of the suffix do in judo has ties to Taoism and Buddhism and in Chinese characters when written means road or way. According to Professor Naoki Murata, Kodokan historian, “The reason that the ju of judo was kept by Professor Kano was out of respect for tradition.” Together judo took on a different flavor. Not only was there a tradition of power but thought, philosophical thought that could aid in the development of a thin emerging nation.

In the case of judo, its meeting was that through its practice, one would develop concepts, skills, and attitudes that would assist one in everyday life situations. Dr. Kano in his writings also emphasizes the idea of small judo versus large judo. Small judo is concerned only with techniques and building of the body. Large judo is mindful of the pursuit of the purpose of life: the soul and the body used in the most effective manner for a good result.

One of Dr. Kano’s more interesting statements concerning education, and in particular, physical education was, “The body is the instrument for the purpose of life, without which there is nothing.” Such a simple but ever so profound statement. The implication is that care must be taken to ensure its proper functioning. In addition, that the mind cannot function, experience, or learn, without having a body. The body is the package in which the mind functions and that their functioning is integrally linked. One Japanese word for experience, taiken, means to experience with the body.

THE JUDO MAXIMS

Although Dr. Kano was widely known as a scholar, there was a side of him which favored experience over knowledge purely based on books. Many of his maxims are derived from life experiences that led to a certain conclusion. David Waterhouse, in his paper, “Kano Jigoro and The Beginning of the Judo Movement” writes, “As far as I can judge, Kano’s thinking evolved to meet the changing circumstances of the movement, which he created”. He was a pragmatist (in a loose sense of the word); and he mistrusted abstract principles, based on book learning. In a note written in 1902 or 1903, he made a distinction between learning, which is alive and learning, which is dead. The former was a practical use, the later serve no purpose. “If one reads books, excessively, even if one does many things, what one knows may or may not be useful, depending on the circumstances.”

“MUTUAL WELFARE AND BENEFIT”

The maxim, Mutual Welfare and Benefit Ji-ta Kyoei, can be thought of as referring to Kano’s concept of the interdependence of body and mind, but more importantly here, the interdependence of one person working with another person. It was the resulting revelation of years of physical practice that enable Kano to understand the benefits of mutual encounters. In Buddhism, the two paths are ji-riki (self strength) and ta-riki (other's strength). In judo, there is also the strength of the individual, which is pitted against the strength of others resulting in a positive change.

The maxim, Mutual Welfare and Benefit Ji-ta Kyoei, can be thought of as referring to Kano’s concept of the interdependence of body and mind, but more importantly here, the interdependence of one person working with another person. It was the resulting revelation of years of physical practice that enable Kano to understand the benefits of mutual encounters. In Buddhism, the two paths are ji-riki (self strength) and ta-riki (other's strength). In judo, there is also the strength of the individual, which is pitted against the strength of others resulting in a positive change.An example is the mutual benefit found in judo’s randori practice, which is done, not by oneself, but with another and results in the eventual development of both individuals. Judo is mindful of this resulting benefit from the practice of two individuals, and thus bow in gratitude and respect before and after the practice session.

JI-KO NO KANSEI

A seldom quoted maxim is that of Ji-ko no Kansei or self-perfection. Most likely ignored because of the seemingly egocentric motives at the time of judo’s mass importation into the United States just after World War II. In addition, the other maxim of Mutual Welfare and Benefit, already has inherent in the word mutual, implication that oneself as well as another is involved.

A seldom quoted maxim is that of Ji-ko no Kansei or self-perfection. Most likely ignored because of the seemingly egocentric motives at the time of judo’s mass importation into the United States just after World War II. In addition, the other maxim of Mutual Welfare and Benefit, already has inherent in the word mutual, implication that oneself as well as another is involved.Today, we are told that we must improve ourselves. Scores of self-help books attests to this fact. The dilemma, however, arises when one asked, “How is it that you can have both self centered act and mutual welfare and benefit at the same time? Doesn't someone lose out when one person thinks of improving himself?” Kano explained it thus. “Needless to say, there is a gap between utopia and the sometimes reality of things. Let's say that rather than two individuals we think on a larger scale and have two countries at war and one of them is your country. Whose side would you favor then?” He continues, “Build yourself first, then you may help others.”

In the short-term, one side they suffer a loss, but both have gained from the experience, and at a later time under different conditions the outcome may be different. One need only think of our next randori practice session or shiai tournament. Who will win? What was gained? Competition tends to breed excellence, and in the long run there is mutual gain from the encounter.

SEIRYOKU ZENYO

Seiryoku Zenyo is commonly translated to mean Maximum Efficiency with Minimum Effort. When Dr. Kano was still a student he found his roommate would always finish his homework earlier and in addition get better grades. Why was it that he had the same amount of homework, as his roommate, same instructors, yet this result? He decided to observe his roommate which eventually resulted in the maxim of Seiryoku Zenyo, maximum efficiency with minimum effort. He states, “In order to study the maxim of Seiryoku Zenyo we must first know what energy is. Energy is life force or the essential force for living. A correct use of this energy will result in maximum efficiency with minimum effort.”

Seiryoku Zenyo is commonly translated to mean Maximum Efficiency with Minimum Effort. When Dr. Kano was still a student he found his roommate would always finish his homework earlier and in addition get better grades. Why was it that he had the same amount of homework, as his roommate, same instructors, yet this result? He decided to observe his roommate which eventually resulted in the maxim of Seiryoku Zenyo, maximum efficiency with minimum effort. He states, “In order to study the maxim of Seiryoku Zenyo we must first know what energy is. Energy is life force or the essential force for living. A correct use of this energy will result in maximum efficiency with minimum effort.”As per energy expenditure and a judo throw, do we expend more energy to throw a person if he is off-balance or on balance? Do we expend more or less energy if we have our center of gravity above or below our opponent’s center of gravity? Do we use energy more effectively if we do the technique quickly or slowly? Is it possible that there is a more efficient way of applying energy? Could one say from this use of energy, one could learn and understand the principle of maximal efficiency with minimum effort?

It is through practical experiences that judoka may learn lessons. The lessons may have to be translated from the practice of judo into words and usable concepts but the body experiences of judo are kept for reference and understood at a very basic level. Here are a few concepts that are realized through practice, and with a little imagination can be translated into usable concepts for everyday living, large judo:

It is through practical experiences that judoka may learn lessons. The lessons may have to be translated from the practice of judo into words and usable concepts but the body experiences of judo are kept for reference and understood at a very basic level. Here are a few concepts that are realized through practice, and with a little imagination can be translated into usable concepts for everyday living, large judo:1. Over a period of time and through diligent practice, one can become better at judo.(at a hobby, sport, work, etc.)

2. There are subtle techniques that allow one person to do better than another person who does not have technique.

3. Although one may not be so skilled to begin with, if one has heart one may still succeed.

4. There are different types of strengths in each of us.

5. Over a period of time we rely on different strengths at different times.

6. That energy utilized in successful ways can instill confidence.

While different ideals may abound within philosophy, it is more an ongoing process rather than a set of immutable ideas. Therefore, it is with the philosophical thoughts surrounding judo. Initially in the martial art of jujitsu, the sole thought was how to kill, maim, or control. At that time, it entailed a philosophy based on survival by hand-to-hand combat. With the opening of Japan, it had to change or disappear. Kano remolded jujitsu. This replacement became a way of life, with lessons in its practice that could be applied to everyday life. He named it judo.

The emphasis of the goals and philosophy of judo have been broadened and while there is a current emphasis towards the idea of judo being a sport concerned mainly with winning and losing, there are still other elements to judo which keep it grounded to the grass roots development of individuals into productive citizens.

Beg. Techniques Key Points

Beginning Judo

- Tachi-waza (Throwing)

- O Soto Gari (Big outside reap)

- Kuzushi

- Step forward with toe equal Uke's heel. Off-balance to the corner

- Tsukuri

- Opposite leg, swing through with straight Leg.

- Kake

- Contact with Tori's back of leg to Uke's back of leg

- Kuzushi

- Ko Soto Gari (Small outside reap)

- Kuzushi

- Off balance to Uke's rear

- Tsukuri

- Tori "shift", "slide" forward

- Kake

- Tori's ball of foot, contact with Uke's heel.

- Kuzushi

- Okuri-Ashi-barai (Foot sweep)

- Kuzushi

- Tori pulls upward and sideways to Uke's body

- Tsukuri

- As Uke's steps sideways, Tori sweeps with foot and making contact with Uke's ankle.

- Kake

- Tori's ball of foot makes contact with Uke's ankle. Important to keep Tori's leg straight on contact with Uke's ankle. Pull continues to be upward and sideways

- Kuzushi

- Harai-goshi (Lifting pull throw)

- Kuzushi

- Uke's front corner

- Tsukuri

- While Uke is moving sideway, Tori steps in same direction, while turning shoulders and hips

- Kake

- Tori points swinging leg and while swing backwards, Tori's back of leg makes contact with Uke's thigh. Tori swing leg, must be straight and firm to transfer power.

- Kuzushi

- Koshi Guruma (Hip throw)

- Kuzushi

- Front corner

- Tsukuri

- Tori's arm wraps around Uke's neck while rotating toward the front of Uke. Tori must bend knees and stay down while rotating.

- Kake

- Tori continues to pull Uke toward the front corner while getting below Uke's center of gravity, Tori extends legs while pulling Uke forwards over Tori's hips.

- Kuzushi

- O Soto Gari (Big outside reap)

- Osae-waza (Pins)

- Kesa Gatame (Regular scarf hold)

- Tori sits on side of Uke, with feet facing opposite position of Uke

- Arm closes to Uke's head, wrap around Uke's neck and secures the grip by holding onto Uke's collar

- Tori's other arm, locks Uke's arm with Tori's armpit and secures the hold by gripping Uke's sleeve.

- Kami Shiho Gatame (Upper four direction hold)

- Tori kneels at Uke's head

- Tori places their arms under Uke's shoulders and secures hold by gripping Uke's obi (belt)

- Tori drops their hips "flat" on the mat, with Uke's head under Tori's armpit.

- Kuzure Yoko-Shiho-Gatame (Modified side hold)

- Tori kneels on the side of Uke.

- Tori's chest is making contact with Uke's chest

- Tori's hand closes to Uke's head wrap under Uke's arm and secures by gripping uke's obi.

- Tori's opposite hand is placed across the body with palm on mat.

- Kesa Gatame (Regular scarf hold)

- Shime-waza (Neck Submission)

- Okuri Eri Jime (collar strangle)

- Tori sits behind Uke with Tori's legs around Uke's waist

- Tori places one arm around Uke's neck securing grip "high" on Uke's collar

- Tori's opposite hand, is placed under Uke's arm and secures grip on Uke's opposite lapel.

- Tori pulls hands in opposite directions

- Kata Ha Jime (single wing strangle)

- Tori sits behind Uke with Tori's legs around Uke's waist

- Tori places one arm around Uke's neck securing grip "high" on Uke's collar

- Tori's opposite hand, is placed under Uke's arm and is placed behind Uke's neck.

- Tori pulls hands in opposite directions

- Gyaku Juji Jime (reversed cross strangle)

- Tori places all four fingers of both hands deeply into the inside of Uke collar with outer sides of both thumbs against Uke left and right carotid arteries.

- When performing this neck submission maneuver, Tori pulls Uke strongly against him, and uses both legs to restrict Uke freedom of movement.

- Okuri Eri Jime (collar strangle)

- Kansetsu-waza (Arm Lock)

- Juji-gatame (Cross Arm Lock)

- Tori drops their knee onto uke to begin controlling them and to prevent them from turning towards tori.

- Tori begins to get better control of uke by squatting, and pulling the elbow of uke tightly onto the chest of tori.

- Tori also places the leg closes to Uke's head, over the head of uke so that uke will not be able to sit up.

- Tori sits down very close to the shoulder of uke so that the arm of uke is still controlled by the body of tori.

- The elbow of uke must be on the abdomen of tori in the final position, so sitting close under the elbow is essential.

- Tori pulls the elbow of uke strongly with their forearm.

- Tori begins to lean back keeping constant pressure on the arm of uke and squeezing the knees together to control the shoulder.

- At this point tori makes sure that the thumb of uke is pointing up so that the pressure will be applied towards the little finger side of the arm.

- Ude-garami (Kimura)

- Tori must bend the Uke's elbow and seize his/her wrist with your hand so that the thumb side or your hand is closest to your opponent's elbow.

- You then reach under the opponent's elbow with your other arm and grab onto your own hand or wrist.

- Uke's hand is facing toward their feet

- Ude-garami (Americana)

- Tori must bend the Uke's elbow and seize his/her wrist with your hand so that the thumb side or your hand is closest to your opponent's elbow.

- You then reach under the opponent's elbow with your other arm and grab onto your own hand or wrist.

- Uke's hand is facing toward Uke's head

- Juji-gatame (Cross Arm Lock)

- Tachi-waza (Throwing)

Int/Adv Techniques Key Points

Tachi-waza

- 1 Kyo

- Hiza-guruma

- Kuzushi

- Tsukuri

- Kake

- Sasae Tsuri Komi Ashi

- Kuzushi

- Tsukuri

- Kake

- Uki goshi

- Kuzushi

- Tsukuri

- Kake

- O soto gari

- Kuzushi

- Tsukuri

- Kake

- O goshi

- Kuzushi

- Tsukuri

- Kake

- O uchi gari

- Kuzushi

- Tsukuri

- Kake

- Hiza-guruma

- Ippon Seoi nage

- Kuzushi

- Pull to bicep

- Lock arm

- Tsukuri

- Rotate into position

- Keep knees bent

- Kake

- Using legs, extend while pulling Uki over shoulder.

- Morote Seoi-nage

- Kuzushi

- Tsukuri

- Kake

- Ippon Seoi nage

- 2 Kyo

- De-Ashi-barai

- Ko soto gari

- Kake

- Kuzushi

- Tsukuri

- Ko soto gari

- Ko uchi gari

- Kuzushi

- Tsukuri

- Kake

- Koshi guruma

- Kuzushi

- Tsukuri

- Kake

- Tsuri komi goshi

- Kuzushi

- Tsukuri

- Kake

- Okuri ashi harai

- Kuzushi

- Tsukuri

- Kake

- Ko uchi gari

- Tai otoshi

- Kuzushi

- Tsukuri

- Kake

- Harai goshi

- Kuzushi

- Tsukuri

- Kake

- Uchi mata

- Kuzushi

- Tsukuri

- Kake

- Tai otoshi

Osae-waza

- Kesa Gatame

- Kami shiho Gatame

- Yoko Shiho Gatame

- Kuzuri kami shiho gatame

- Kata gatame

- Tate shiho gatame

Shime-waza

- Name-juji-jime

- Okuri-eri-jime

- Gyaku juji jime

- Hadaka jime

- Kataha jime

Kansetsu-waza

- Juji-gatame (Cross Arm Lock)

- Ude-garami (Americana)

- Ude-garami (Kimura)

- 1 Kyo

How to Score a Judo Match

Scoring of a Judo Match

Objective

In Judo competition the objective is to score an Ippon (one full point). Once such a score is obtained the competition ends. An Ippon can be scored by one of the following methods:

- Executing a skillful throwing technique which results in one contestant being thrown largely on the back with considerable force or speed.

- Maintaining a pin for 20 seconds.

- One contestant cannot continue and gives up.

- One contestant is disqualified for violating the rules (hansoku-make).

- Applying an effective armbar or an effective stranglehold (this does not apply for children).

If the contest time expires the contestant with the highest score will win. In the event neither contestant scored or the score is tied, the contestants will enter into "Golden Score". The first opponent scoring will win the match.

If the contest time expires the contestant with the highest score will win. In the event neither contestant scored or the score is tied, the contestants will enter into "Golden Score". The first opponent scoring will win the match.“Ippon”

When a contestant scores ippon, the referee shall announce, “Ippon” the match is over. The contestant scoring ippon is the winner. An ippon can be scored in both tachi-waza (standing) and ne-waza (groundwork).

When a contestant scores ippon, the referee shall announce, “Ippon” the match is over. The contestant scoring ippon is the winner. An ippon can be scored in both tachi-waza (standing) and ne-waza (groundwork).Should one contestant be penalized “Hansoku make” (major penalty infraction) the other contestant shall be declared the winner.

Ippon is scored when: A contestant with control throws t

he other contestant largely on his back with considerable force and speed.

he other contestant largely on his back with considerable force and speed.Contestant gives up by tapping twice or more with his hand or foot or says “Maitta” (I give up), shime waza (strangle) or kansetsu-waza (armlock).

“Wazari”

Waza-ari is scored when: A contestant throws the other contestant with control, but the technique is partially lacking one of the elements necessary for ippon, or a contestant holds with osaekomi-waza the other contestant who is unable to get away for 10 to 19.9 seconds.

Waza-ari is scored when: A contestant throws the other contestant with control, but the technique is partially lacking one of the elements necessary for ippon, or a contestant holds with osaekomi-waza the other contestant who is unable to get away for 10 to 19.9 seconds.Golden Score

If the score is even at the end of the time allowed for a match, usually there will be a Golden Score period where the timer will be reset and the first contestant to score any point wins.

“Osaekomi”

The referee shall announce “Osaekomi” when the contestant being held is controlled by the opponent. You must have the opponent back, both shoulders, or one shoulder in contact with the mat. Control can be made from the side, from the rear, or from the top.

The referee shall announce “Osaekomi” when the contestant being held is controlled by the opponent. You must have the opponent back, both shoulders, or one shoulder in contact with the mat. Control can be made from the side, from the rear, or from the top.“Toketa”

The contestant applying the hold must not have their leg(s) or body controlled by the opponent’s legs. If the contestant being held down can escape by NOT allowing their back or shoulders be in contact with the mat, the referee would announce “Toketa” the pin is broken and the Osaekomi time stops.

The contestant applying the hold must not have their leg(s) or body controlled by the opponent’s legs. If the contestant being held down can escape by NOT allowing their back or shoulders be in contact with the mat, the referee would announce “Toketa” the pin is broken and the Osaekomi time stops.Tournament Management: Timer/Scoreboard

Timer/Scoreboard

- Golden Score

- Back/Undo

- New Contest

- Shido penalty for Blue Contestant

- Yuko score for Blue Contestant

- Wazari score for Blue Contestant

- Ippon score for Blue Contestant

- Start/Stop/Sonomama

- Osaekomi

- Osaekomi Reset

- Yuko score for White Contestant

- Wazari score for White Contestant

- Ippon score for White Contestant

- Shido penalty for White Contestant

Tournament Management: Referee Hand Signals

Referee Hand Signals during competition (Shiai)

- Nage-waza (Throws)

- Ippon

- The referee shall raise one arm with palm of hand facing forward, high above the head.

- When a contestant with control throws the other contestant largely on his back with considerable force and speed.

- When a contestant holds with osaekomi-waza the other contestant for 20 seconds.

- When a contestant gives up by tapping twice or more with his hand or foot or says maitta.

- When a contestant is incapacitated.

- Equivalence: Should one contestant be penalized hansoku make the other contestant shall be declared the winner.

- Wazari

- When a contestant with control throws the other contestant, but the technique is partially lacking in one of the four elements necessary for ippon.

- When a contestant holds with osaekomi-waza the other contestant who is unable to get away for 10 seconds or more, but less than 19.9 seconds.

- Ippon

- Osae-waza

- Osaekomi (Pin)

- To indicated a hold down is on. The referee shall point his arm out from his body down towards the contestants while facing the contestants and bending his body towards them.

- Ippon: total of 20 seconds.

- Waza-ari: 10 seconds or more but less than 19.9 seconds.

- Toketa (Escape)

- To indicate a hold-down is broken, the referee shall raise one of his arms to the front and wave it from right to left quickly two or three times while bending the body towards the contestants.

- Osaekomi (Pin)

- Penalty (Shido)

- To award a penalty (shido or hansoku-make), the referee will make the signal for the appropriate penalty and then point towards the offending contestant with the index finger extended from a closed fist.

- Nage-waza (Throws)